The post Unlocking the secrets of survival at the edge of environmental extremes appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

DR. HEATHER GAINFORTH HAS ONE SIMPLE QUESTION whenever she starts her research: “How can I help?”

In her work with the spinal cord injury (SCI) community, Dr. Gainforth conducts research she hopes will change how other research partnerships are done, by having them include more meaningful, real-world engagement with the communities who would benefit from the work.

“I’m interested in why people do what they do,” says Dr. Gainforth, an Associate Professor in UBCO’s School of Health and Exercise Sciences. “My work asks two questions: ‘How do you change behaviour?’ and ‘how do you do it in a way where the research ends up in the real world?’”

This desire to apply research to the real world started with Dr. Gainforth’s master’s thesis on exploring health messaging. The discovery of a vaccine for the human papillomavirus—approved by the American Food and Drug Association in 2014—had the potential to prevent cancer, yet students at her university hadn’t heard of it.

Dr. Gainforth asked why.

“There’s a 17- to 20-year gap from when research is done to when it’s used in practice,” says Dr. Gainforth, who initially shied away from becoming a professor because of this significant delay. She soon realized she had a passion for knowledge translation—or the movement of research from the lab into the hands of people who can use it.

Dr. Heather Gainforth with her research team and partners from Kelowna’s spinal cord injury community.

During her doctoral research at Queen’s University, Dr. Gainforth started working with Peter Athanasopoulos, Director of Public Policy at Spinal Cord Injury Ontario, and someone living with a spinal cord injury himself. He said if she wanted to do research with people with SCI, it would need to be a true partnership where she listened to the community.

She enthusiastically agreed. By the end of her degree, the pair had shared guidelines across Ontario and Dr. Gainforth had a new understanding of knowledge translation—or, how meaningful partnerships are key to applying research in communities who need it.

When Dr. Gainforth arrived at UBCO, she contacted Spinal Cord Injury BC, Alberta and Ontario to learn what she could begin doing to help right away. As a result of that partnership, the SCI organizations were able to use her approach to translate the research into practice more quickly to address real-world needs.

Then, they asked her to do something bigger.

“They said, ‘We need more people doing research the way you do it,’ said Dr. Gainforth. “That turned my behaviour change brain on. They wanted me to change the behaviour of other researchers.”

Working with a multidisciplinary group of partners, including SCI researchers, clinicians and people with SCI, Dr. Gainforth’s team developed guiding principles for research partnerships to conduct quality and ethical research that is relevant, useful and avoids tokenism. The principles are to be used by all partners early and throughout the research process.

Dr. Gainforth says if her work can help support researchers to meaningfully engage, we can close huge research gaps and help turn research into reality. “I’m of the belief that research is not complete until it has a real-world impact.”

The guiding principles apply to areas in health research within, and beyond, spinal cord injury, including exercise counselling, peer mentorship and bowel and bladder care intervention, meaning more people than ever can benefit from her expertise.

Her work has been accessed across Canada and in nearly 40 countries, with researchers around the world adopting her principles. This national and international impact led Dr. Gainforth to be named UBC Okanagan’s 2023 Researcher of the Year in Health.

“At UBC Okanagan, there’s a lot of support around doing this work and thinking, ‘How do we ensure that what we’re doing involves a community-engaged approach?’ UBC’s strategic plan speaks to this sense of community engagement and that’s exciting for me, because I have the opportunity to help every researcher on campus.”

In her Applied Behaviour Change Lab, Dr. Gainforth is now training the next generation of scientists to consider partner feedback before all else. “When a student in our lab proposes a study, the first question I ask is: ‘What does the community think about that?’”

The post Partnering for meaningful impact in the spinal cord injury community appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

Describe your research. What inspired you on this path?

I chose to study human kinetics because I’m interested in understanding how diet and exercise can help reduce an individuals’ risk for developing chronic diseases. I’m currently completing my undergraduate honours thesis with UBCO’s Diabetes Prevention Research Group under the supervision of Dr. Mary Jung.

The prevalence of chronic diseases is increasing across Canada. Although chronic disease prevention programs are designed to help improve health outcomes through adoption and adherence to good diet and exercise behaviours, these programs rarely reach equity-deserving groups who are most at risk for developing chronic diseases.

My study is critical for improving demographic data collection practices in community-based prevention programs, so that we may better understand the populations being served and identify inequities in program delivery. With improved demographic data, programs can develop better solutions for increasing the equity of care.

What do you think makes UBCO unique?

UBCO is an amazing place to learn and study. My favourite part about being here is the close-knit community. I love being able to walk across campus and wave to classmates or have my professors ask me how I’m doing when passing by. UBCO is a supportive environment that wants to see you succeed and thrive; I don’t feel like I’m just another undergrad student here, but rather, a valued member of the campus community.

What are some challenges you’ve faced so far in your academic career?

A big challenge I face regularly is balancing academics and my personal life. I’ve dealt with burnout in the past, so I know the consequences of not listening to your body. It takes trial and error to find the strategy that works best for you. I’m better at finding this balance now than I was in my first year, but it’s still difficult at times. I think a big thing I’ve learned is that by taking the time to rest when you need it, you’re helping yourself in the future.

“I hope to one day mentor undergraduate researchers and help them learn just how rewarding research can be—something my mentor has done for me.”

What does it mean to you to be a Stober Foundation Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) recipient?

Being a SURF recipient is an incredible opportunity; I had the wonderful experience of working in the Diabetes Prevention Research Group, a laboratory focused on community-based health programs and improving equity in access to Type 2 diabetes prevention care. I gained valuable research skills and learned about collaboration, communication, problem solving, time management and mentorship—skills that will serve me in any future career.

Do you have a mentor? If so, how have they influenced you?

I’m very lucky to have a mentor who has helped guide me through the last two years of my degree. Having a mentor with similar experiences is great when you need someone to talk to about the challenges and struggles you’re facing. Whenever I’m feeling overwhelmed, I speak with my mentor, and they offer me new perspectives and clarity. I hope to one day mentor undergraduate researchers and help them learn just how rewarding research can be—something my mentor has done for me.

What’s the best advice you have for new undergraduate students?

Get involved in a wide variety of activities and projects! Get involved in things on campus, off campus, within your faculty or in a different faculty! By getting involved in a variety of projects, you learn new skills and meet new people. Being involved on campus also makes your university experience more than just academics; it’s about being a part of a community.

What do you hope to do after finishing your undergrad?

I want to continue to do research and stay with UBCO for my Master of Science. My passion for research is driven by my passion to help others live long, healthy lives. I want to do work that makes a difference to others, and I see the importance my research has in doing that. My long-term career goal is to keep focused on improving health promotion and preventative care.

The post Sarah Craven is learning valuable research and career skills appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

IN A SMALL ONTARIO TOWN MID-WAY BETWEEN TORONTO AND WINDSOR, a young Dr. Jennifer Jakobi figure skated, danced and ran track, with aspirations of one day becoming a coach and high school physical education teacher. For the Faculty of Health and Social Development professor, a career as an exercise neuroscientist could not have been further from her radar.

“I was so fortunate to have someone in my life who recognized how I lit up when I was involved in science during my undergrad,” Dr. Jakobi says. “Although I laughed at them and tried to discourage the idea of pursuing it.” It was this mentor’s partner—a school principal—who made all the right arguments, and Dr. Jakobi soon put teaching on hold in favour of a master’s degree in exercise science.

“I followed some sage advice when choosing my master’s degree,” she says. “More so than the field you choose for a master’s, it’s important to make sure you like the person you’re working with; that you can get along with them and be mentored by them. For me, it was Dr. Enzo Cafarelli at York University. A bigger-than-life personality, he got me hooked on human motor science, especially motor unit physiology, and that was the start of my academic journey.”

“Dr. Jakobi has been instrumental in helping me further my research. While encouraging independence in her lab, she is tremendously supportive of her students, and it’s clear she values and actively seeks to facilitate student success and personal growth opportunities.”

Mentorship is something Dr. Jakobi has valued throughout her career—not just as a mentee, but as a mentor—and she doesn’t hesitate to say that her students are the heart of her research. School of Health and Exercise Sciences master’s student Eli Haynes has worked with Dr. Jakobi in her Healthy Exercise and Aging Lab for the past few years. “Dr. Jakobi has been instrumental in helping me further my research,” he says. “While encouraging independence in her lab, she is tremendously supportive of her students, and it’s clear she values and actively seeks to facilitate student success and personal growth opportunities.”

As a way to increase opportunities for girls to experience science, Dr. Jakobi developed the integrative STEM Team Advancing Networks of Diversity (iSTAND) program in 2014. It has since grown to embrace intersectionality and strives to remove labels from learning environments.

“It doesn’t matter who you are,” she says. “People are people. We’re engaging with youth, families and teachers to build an inclusive environment.” She applies this approach to her role as the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC)-sponsored Chair for Women in Science and Engineering. Dr. Jakobi is one of five national chairs. And for the BC and Yukon Region, the West Coast Women in Engineering, Science and Technology (WWEST) program aims to empower individuals to make organizational change.

“Through iSTAND and WWEST, we’re going to build a vibrant community of diverse individuals to advance science and generate knowledge.”

The motor unit

“Motor units are individual nerves that exit the spinal cord and go to many muscle fibres,“ explains Dr. Jakobi. “They’re the final neural element of controlling movement.” She adds with a smile that she could study it until she retires. “But there’s more to it than contributing to the scientific literature.”

An older adult study participant once posed the question during her PhD, “Why does this matter to me?” After some deep introspection, Dr. Jakobi realized that what she does in the lab ultimately needs to benefit people.

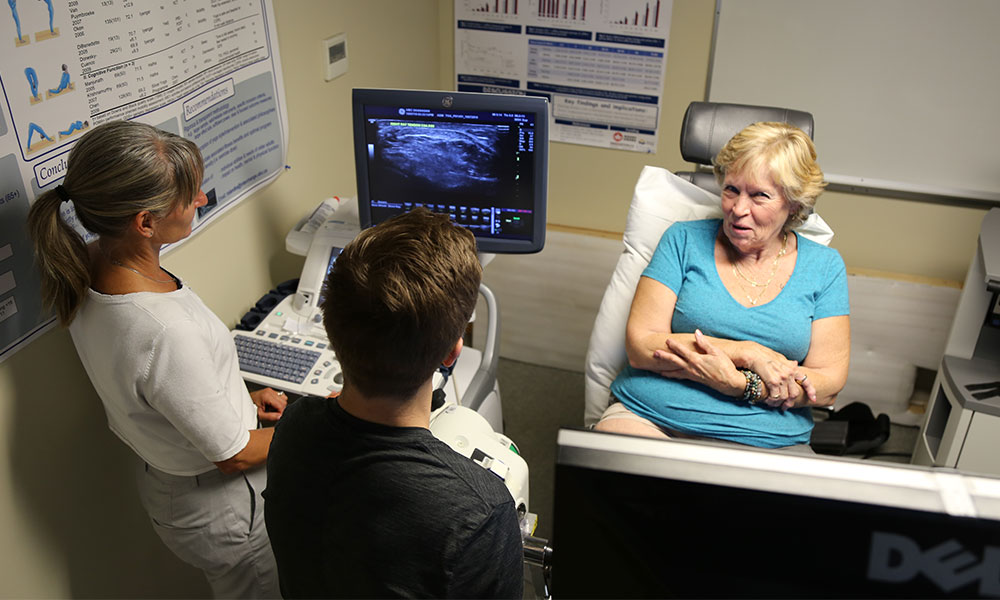

Dr. Jennifer Jakobi (left) in the lab.

In her NSERC research program, Dr. Jakobi’s team seeks to realize how sex-specific differences influence the adult aging process. “Our hope is that by understanding neuromuscular adaptations between men and women, we can hone in on specific areas of focus when it comes to lessening functional decline for a man or a woman.”

Dr. Jakobi uses the example of an older man and woman who don’t have the strength to stand up from a chair. “Sex-specific physiological differences exist, so to prevent functional decline with increased age we recommend resistance training for the woman starting in her 40s or 50s. For the man, this might be put off until he’s in his 60s for both of them to experience the same net abilities with increased age.”

Campus collaboration

A highlight of Dr. Jakobi’s recent career has been leading the Aging in Place Research Cluster. The cross-campus collaboration brings together a dynamic team of engineers, psychologists, health and behavioural researchers and volunteer study participants to understand what older adults need and want.

“We want to figure out the physiology that will support those needs and wants, and to use that physiology to inform interventions, self-management, and the design and engineering of products. This is where the work is collaborative, but encompasses the older person.”

She adds: “What I love about it is that we’re able to look at things from a societal perspective. We’ve really engaged with older adults in our research planning.” Key initiatives of the cluster help older adults retain functional independence, improve social connections and promote their physical activity.

“One thing I really appreciate about UBC Okanagan’s smaller campus,” Dr. Jakobi says, “is how many close friends and colleagues I’ve developed. If I need the expertise of someone from a particular faculty, I don’t have to go to a website, I can just pick up the phone and call someone I already know in that faculty.”

UBC Okanagan’s close-knit community also offers the type of teaching environment that Dr. Jakobi relishes. “The smaller environments allow for a real connection with the next generation of scientists and leaders,” she says. “It’s the connection of science impacting life and life impacting science. When students make connections in the lab that are genuine from a place of learning, that’s what I love about teaching.”

She adds: “People are here because they want to make a positive change. They want to keep an institution at the heart of the people, with the people and for the people. UBC Okanagan has a small-town attitude but on a grand scale of international influence through its teaching and research.”

The post Dr. Jennifer Jakobi brings people together with a purpose appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

The post A Rebalancing Act appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

The post Research with Altitude appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

WHEN CIRCUMSTANCES ADVANCE AND CONVERGE BY CHANCE in such a way that an outcome is favourable, we like to call it serendipity. When UBC Okanagan student Dr. Rhyann McKay came across a way to combine her passions for psychology, political science and health, she called it HMKN 421 (Human Kinetics: Advanced Theories of Health Behaviour Change).

“Dr. Heather Gainforth’s course was the first class that tangibly spoke to me,” says Dr. McKay. “It linked my interests in psychology, designing policy and helping people do the things that support their health. Ultimately, it was the health promotion aspect of human kinetics that piqued my interest, and Dr. Gainforth ended up becoming my PhD supervisor.”

The world was Dr. McKay’s oyster coming out of high school, with opportunities at the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta ripe for the picking. However, during a visit with a friend attending UBC Okanagan, Dr. McKay decided where she wanted to pursue her post-secondary education. Although people attend UBCO for a variety of reasons, like being a world-renowned research university, Dr. McKay simply fell in love with the campus.

“It’s just so beautiful,” she says. “The close-knit and collaborative community and intimate learning environments provide opportunities for deep connections with professors and other researchers. As a student your voice is never drowned out like it might be in a class of 500 peers. The close proximity to Big White for snowboarding and Myra Canyon for mountain biking was also very appealing. Looking back, I know I made the right decision.”

She adds that the Centre for Health Behaviour Change, where she spent much of her time, is a special place. “It’s the home of phenomenal researchers and phenomenal women in research like Dr. Gainforth, Dr. Kathleen Martin Ginis and Dr. Mary Jung. I had the opportunity to learn from each of them and they continue to be very important to me.

“My PhD program aimed to develop and examine a behavioural counselling intervention for family support providers of people with spinal cord injury,” says Dr. McKay. A key component of her research was pinpointing behaviours that were impacted when family members or partners were put in a support-providing role. “We looked for enablers to those behaviours we want more of, and for barriers to those behaviours. Then we could address and support those factors through behaviour change techniques.”

Some of those techniques include goal setting, action planning and problem solving, which aim to address hurdles like managing time and competing priorities. The end product of Dr. McKay’s program was a behavioural counselling intervention that addressed self-care behaviour. “This could be anything that people do for themselves and no one else, from the most basic, like bathing and socializing, to getting out and exercising.”

Dr. McKay is a firm believer that research should start with the question: How can I help? During her study, she interviewed many families and partners of people with spinal cord injury who identified the need for additional tools and sources of support. “That was when I knew I was on the right track,” she says.

“Through an integrated knowledge translation approach, we equitably and meaningfully partner with people who will use the research in the end,” explains Dr. McKay, who conducted her study in partnership with Spinal Cord Injury BC, Spinal Cord Injury Alberta and Spinal Cord Injury Ontario. “These are pivotal organizations that support persons with spinal cord injury and their families, and were very instrumental during my research.” She adds: “The mentorship I received from members of these organizations was critical beyond academia.”

Dr. McKay has been recognized with UBC Okanagan’s Student Researcher of the Year award for her leading-edge research in partnership with provincial spinal cord injury organizations across Canada to co-develop behaviour change interventions.

“When I was deciding what to do after my undergrad, a mentor told me how important it was to find my joy,” Dr. McKay says. “They suggested I follow my passion and do what makes me truly happy. My heart is in conducting research that can be directly used by the people it impacts. It’s fun and exciting and I’ve found joy and meaning in the work.”

The post Dr. Rhyann McKay begins with the question: “How can I help?” appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.