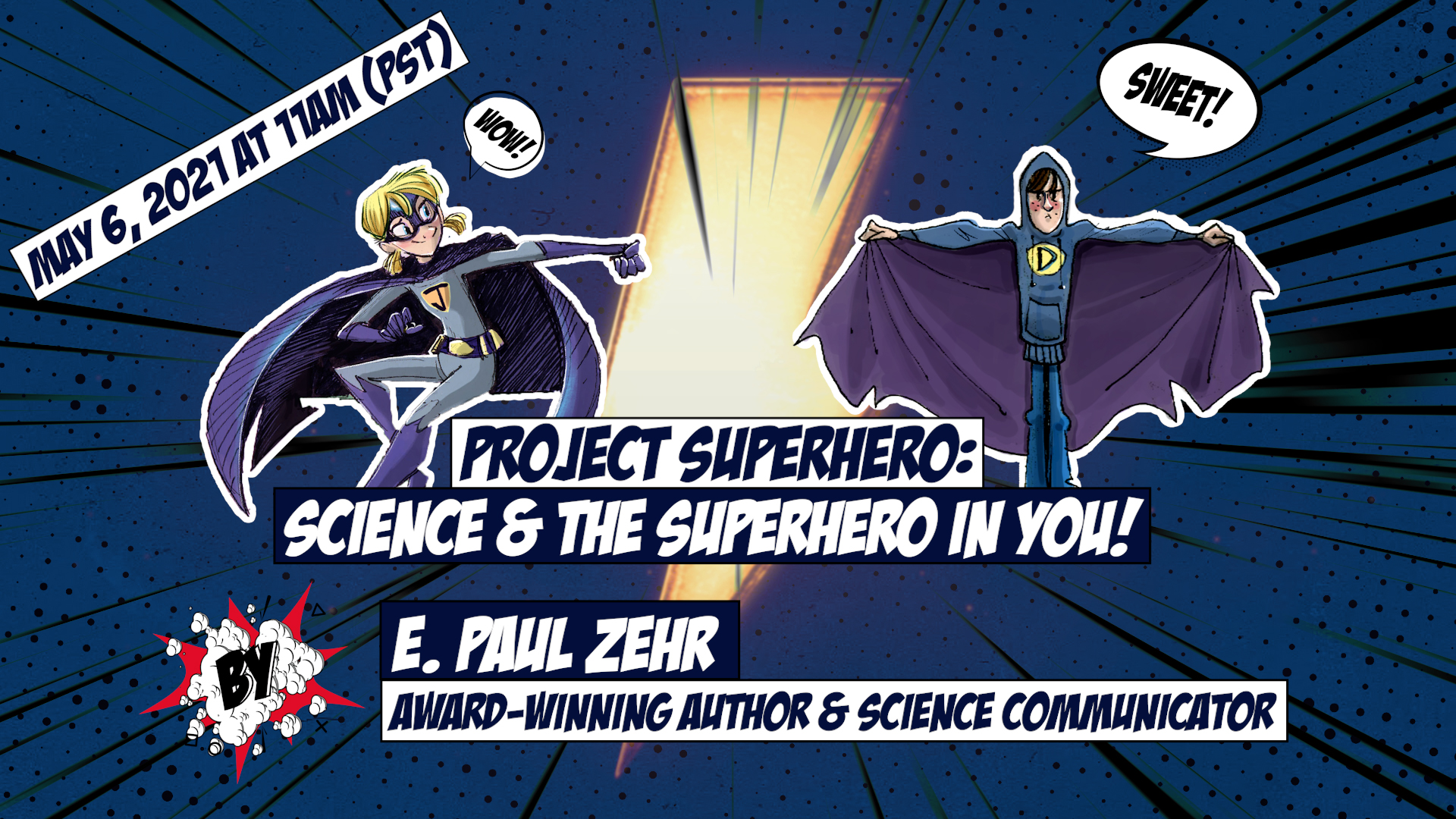

UBC Okanagan’s School of Health and Exercise Sciences is pleased to welcome award-winning author and science communicator Dr. E. Paul Zehr.

You’re invited to join.

When: May 6, 2021, 11 a.m. PST (2 p.m. EST)

Where: online

What: Engaging online talk designed for ages 7-12

Find the superhero in you!

Event proudly supported by iSTAND

iSTAND is proud to present STEM activity videos to introduce youth to neuroscience, develop counting and math skills, and explore STEM! Each of our videos have an accompanying worksheet to support learning and deeper understanding of concepts, as well as provide adaptations to the activities.

About Dr. E. Paul Zehr

Dr. E. Paul Zehr is a Professor and is currently the Director for the Centre for Biomedical Research at the University of Victoria. Dr. Zehr heads the Rehabilitation Neuroscience Laboratory and authors the blog Black Belt Brain. Dr. Zehr is passionate about the popularization of science using superheroes as foils for human achievement and ability. His recent pop-sci books include BECOMING BATMAN (2008), INVENTING IRON MAN (2011), PROJECT SUPERHERO (2014), and CHASING CAPTAIN AMERICA (2018).

Paul Zehr has a passion for sharing knowledge of moving, martial arts, and the mind. His earliest scientific studies were on martial arts, but shortly into his scientific career, he shifted to the neural control of movement and rehabilitation of walking after stroke and spinal cord injury. Now he is working to see if martial arts training can help with balance, walking, and self-efficacy in Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, and after stroke. His passion began early in his career, when Dr. Zehr was studying walking like most other researchers: by focusing on the legs. It wasn’t until he drew an armless stick figure for an article that he realized how odd it was to ignore arms in a study of walking. Since all other mammals move their forelegs in a coordinated manner with their hind legs, why not humans? Thus, a simple armless stick figure propelled Dr. Zehr into his study of coordinated movement.

Dr. Zehr is well-known for his innovative work, and won the 2012 Craigdarroch Award for Research Communications at the University of Victoria and the 2015 Science Educator Award from the Society for Neuroscience. “Project Superhero” received the 2015 Silver Medal for Juvenile Fiction from the North American Independent Book Publishers.

The leg bone is connected to the arm bone

Early in his career, something strange occurred to Dr. E. Paul Zehr about his specialty. Zehr is a neuroscientist studying, among other things, how to teach people to walk again. He was drawing a stickman diagram for an article on the neural control of walking when he realized his stickmen had no arms.

Armless stickmen were the convention at the time, because as Zehr explains, it is only natural for a neuroscientist studying walking to focus on the legs. But looking at his stickmen, it suddenly occurred to Zehr that totally ignoring the arms was odd.

In all other mammals, the forelegs move in a pattern with hind legs. For instance, if a cat’s forepaw slips into a hole, a neural message will go to the back paw telling it to get ready. The cat’s limbs move as a unit. Could humans be the same?

Zehr realized that just because humans’ arms are not obviously involved in walking, they probably are.

He also foresaw a new avenue for rehabilitation: arm exercises could help people control their legs.

Ten years later, working first as a assistant professor in the Faculty of Physical Education & Recreation and Centre for Neuroscience at the University of Alberta, and then as a Associate Professor in the Rehabilitation Neuroscience Laboratory in the Faculty of Education here at UVic, Zehr has confirmed his initial insight.

Specifically, Zehr measures how arm and leg reflexes change over a cycle of rhythmic movement such as swimming, walking or cycling.

He uses cycling as a model. As his test subjects cycle on a stationary bike for arms and legs, he uses electrodes to stimulate various nerves that go to the skin and muscle of the arms and legs. He then looks for reflexes by measuring muscle activity in the arms and legs. This method serves as awindow into the state of the nervous system of his subject during cycling.

He found that in humans, just like in other mammals, the brain and spinal cord coordinate all four limbs as a unit. Reflexes in the legs will change depending on if the arms are moving and vice versa. Also, both arm and leg reflexes change their character throughout the cycle of movement.

The first stage of Zehr’s work has been to find the neural connections between arms and legs in healthy humans.

The second is to see if these connections are broken or lost in people who have had strokes or spinal cord injuries. Zehr has just begun this work with some hopeful findings: portions of the connections coordinating arms and legs are still present in stroke victims. That means the remnants of these neural pathways can be strengthened.

The next stage of research is to test whether exercises that coordinate arms and legs can help stroke victims recover.

Zehr finds this real-world application exciting. Yet his work is also expanding the general knowledge of human movement and even how movement evolved. Zehr has found that human movement is both similar to monkeys and to horses, and yet we are unique in our ability to uncouple movement between our limbs.

It turns out that spinal central pattern generators (CPGs) are evolutionarily conserved across all species, spanning the swimming lamprey, the crustaceans, the cat, non-human primates, all the way to our own species. CPGs are networks of neurons in the spinal chord that generate a simple locomotor rhythm. The flexible coupling of CPGs responsible for each arm and leg in humans is what gives us our ability to perform a variety of movements like walking, running, cycling and swimming.

One thing is certain: Zehr’s stickman diagrams have evolved to include arms.